Guest post by Louie Wheeler

The pharaohs of the Egyptian New Kingdom made a habit of rewriting history. Through a process defined as ‘usurpation’, rulers routinely altered, often by adding their own titulary, or destroyed their predecessors’ monuments, reliefs and statues. Where we see evidence of destruction, the aim is clear: to erase aspects of the past, or at least present them in a negative light. The reigns of ‘illegitimate’ rulers were often wiped from the historical record in order to help the incumbent pharaoh secure their own position. This process has become known as damnatio memoriae, meaning ‘the condemnation of memory’.

We have plenty of evidence for damnatio memoriae being conducted at the highest echelon of Egyptian society by the pharaoh, in the form of defaced statues, temples and inscriptions. The above image, from Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, is but one example of the name and titulary of an earlier ruler being hacked away, and the kind of highly localised damage seen here is one of the telltale signs of a usurped monument. In other examples, we see old cartouches flattened out and replaced with the name of another king, and statues sometimes altered to resemble a different king. Through this process, New Kingdom pharaohs could keep tight control over the historical narrative, which helped them both legitimise their own reigns and ensure that the title of pharaoh itself remained strong and stable.

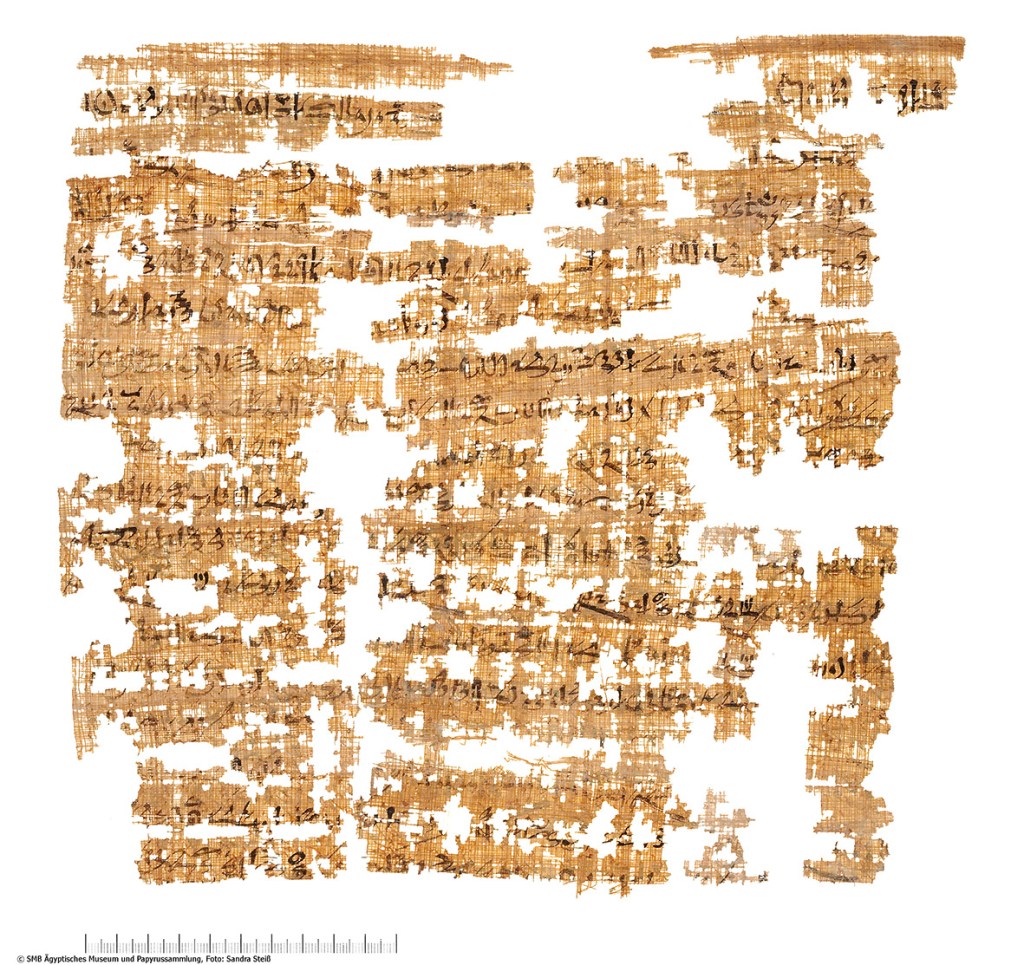

However, these are obviously very large-scale, visible displays, and as Polly Low argues, the aim of these very noticeable acts of erasure may not so much have been to completely obliterate the memory of an individual, but to vilify them, and make the viewer consider why that individual needed to be subject to such an act. However, there is one object, currently in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, which could offer another interpretation. Measuring around thirty square centimetres, it is a letter, written in hieratic, the standard Egyptian script at the time. The letter was addressed to the ‘Prince’ or ‘Mayor’ of Thebes, named Paser, at some point during the reign of Ramesses II (1279 – 1213 B.C.E). Unfortunately, the papyrus is in quite a sorry state, yet what can still be read from these few fragmentary remains is highly valuable. Lines 6 and 7 particularly stand out, reading:

Further, as to what you write to me asking that the day of […]’s death should be sent to you, when one (i.e. Pharaoh?) arrived in Memphis, [the … came to me] to say that he died in year nine of the Rebel.

(ÄM P.3040; trans. by Gardiner 1938)

This part of the letter responds to what must have been an earlier request from Paser for the date of an individual’s death. In a case like this, where the mention of a specific year was needed, people would normally refer to the regnal year of the pharaoh on the throne at that time. However, in this letter, a ruler’s name is not given, and instead the writer refers to a ‘rebel’ king. In another case, also from during the reign of Ramesses II but inscribed at Mehu’s tomb in Saqqara, a court record refers in a similar way to ‘that damned one of Akhetaten’. This is an example of ‘nonmention’, where, as the term implies, an individual was simply omitted from any future records. In the case of P.3040 the allusion is very vague, but it had enough similarities to the inscription at Saqqara for Alan Gardiner (1905) to conclude that both referred to the so-called ‘heretic king’, Akhenaten.

Ironically, Akhenaten’s reign is well known today. Assuming the throne as Amenhotep IV, he changed his name four years later to reflect the drastic changes to Egypt’s religion he planned to enact. In the place of the existing polytheistic system, the pharaoh promoted the sole worship of the Aten, portrayed as a life-giving sun disc, and as part of this program he usurped many temples and monuments, erasing the names and images of other gods, mainly Amun and Mut. We have little evidence that might shed light on Akhenaten’s motivations, but, whatever the reason, we know his changes were unpopular. After his death in 1336 B.C.E, just as he himself had defaced imagery of the old deities, his monuments were destroyed, including his new capital city, Akhetaten, which lay at the modern-day site of Amarna. The years of his reigns, and those of his immediate successors (including, most famously, Tutankhamun) were later attributed to the pharaoh Horemheb, in king lists such as that in the temple of Seti I at Abydos. In doing so, the heretic was expunged from history.

This is a rare example of damnatio memoriae filtering down throughout wider Egyptian society. But this papyrus is intriguing for more reasons. The fact that the mere mention of Akhenaten became something of a taboo shows that the aim of the damnatio memoriae against him was likely to erase his very existence from the historical record, and to ascribe the chaotic Amarna period to the work of a nameless, illegitimate rebel, rather than that of a king. Clearly this period was so deeply unpopular, and such a stain on the institution of pharaoh, that it was necessary for later rulers to take this step. Yet, despite his successors’ best efforts, as this allusion to him proves, it was clear that Akhenaten was never fully forgotten. It is also not clear whether it was the king or the people themselves who mandated this nonmention. One thing that is plain is that there is still a lot more that needs to be understood about the process of damnatio memoriae in ancient Egypt.

Technical Details

Provenance: West Thebes, Egypt

Date: New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, Reign of Ramesses II (1279 – 1213 B.C.E)

Language: Late Egyptian (Hieratic script)

Collection: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection (P.3040)

Designation: ÄM P.3040

Bibliography: Alan H. Gardiner, ‘A Later Allusion to Akhenaten,’ The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 24 (1938) p. 124; Donald B. Redford, Akhenaten: The Heretic King (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984) pp. 227-31.

Additional Bibliography: Peter Brand, ‘Usurpation of Monuments’, in UCLA Encyclopaedia of Egyptology, ed. Willeke Wendrich (Los Angeles, 2010) [online]; Polly Low, ‘Remembering, forgetting, and rewriting the past: Athenian inscriptions and collective memory,’ Histos, Supplements 11 (2020), pp. 235-68 (p. 245); ; Alice McClymont, ‘Historiography and methodology in the study of Amarna Period erasures’ in The Cultural Manifestations of Religious Experience: Studies in Honour of Boyo G. Ockinga ed. Camilla di Biase-Dyson and Leonie Donvovan (Munster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2017) pp. 31-42; Alan H. Gardiner, The Inscription of Mes: A Contribution to the Study of Egyptian Judicial Procedure (Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1905) p. 11.