Jennifer Cromwell

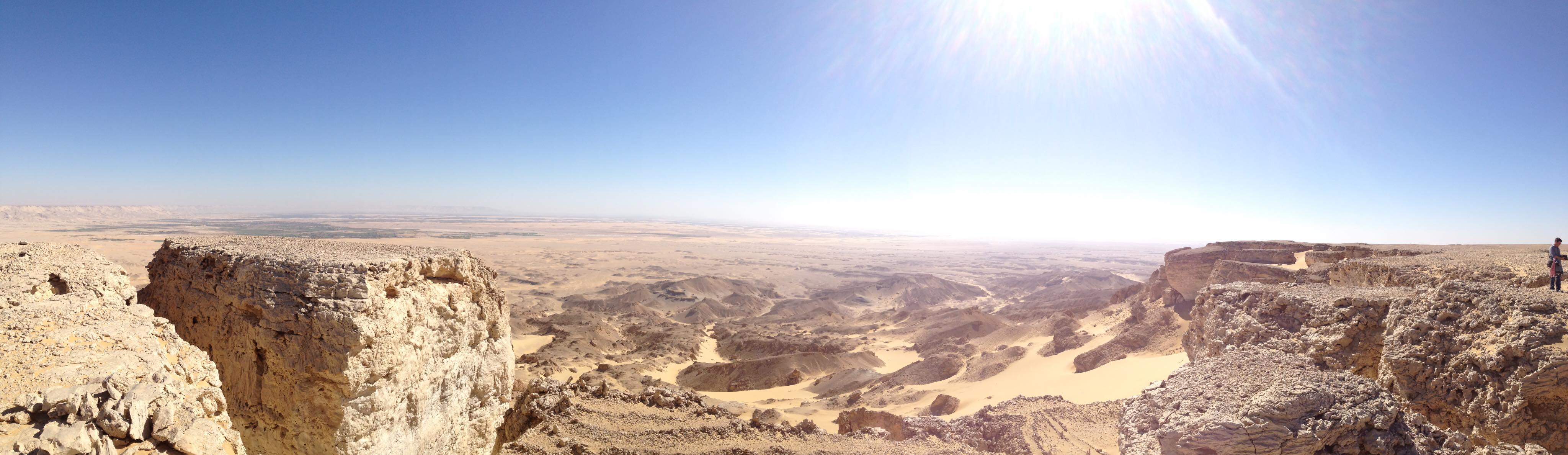

Life in the ancient world, before the development of modern medicine, was hard. Child mortality rates were high, life-expectancy was much lower than it is today, and illnesses and injuries that are easily cured now were often fatal. Life out in the oases of the western desert must have been especially difficult.

For the past three decades, a team of researchers from Monash University led by Colin Hope have excavated the village Kellis, modern Ismant el-Kharab, in Dakhleh Oasis. This work resulted in the discovery of hundreds of Greek and Coptic documents, as well as a smaller number written in Syriac, found within buildings of the village and dating to the fourth century CE. They provide insights into different aspects of the lives of the inhabitants, mostly contained in letters that villagers wrote to family members working in the Nile Valley. The letters are full of details about daily affairs going on at home, keeping the absentees up-to-date with what they were missing. Among the business matters that are related, and general greetings, are topics of a less happy nature.

In one letter, the woman Tegoshe writes to her *brother Pshai of tragic events that prevented her from leaving the oasis:

“The children of Nonna fell ill and died. I, myself, developed pus and have not been able to come. But, you, my brother, do not forget me! Rather, just as you took care of me here, do not abandon me now! Greet me warmly to my lady, my sister Tapshai. Tell her that I was set to come to Egypt, myself and the little girl. Then death forced itself on me and carried her away. I am powerless! It is not only her – Nonna’s children have also died.”

P.Kellis VII 115

In an earlier letter (P.Kellis VII 92), Timotheos tells his *sister Kyra that “Our sister Nonna and her daughters are all well.” So what happened between the writing of these two letters? Did the girls succumb to a wider epidemic blighting the community? Or are their deaths reflective of child mortality rates in the ancient world? This textual evidence can be compared with the human remains from the Kellis 2 cemetery, where 61% of the 635 burials are for juveniles. The human remains have been the subject some studies, but continuing work and future publications will hopefully reveal more about health issues and causes of death.

Not only children died unexpectedly. In P.Kellis VII 73, Pegosh writes to Pshai:

“I greet you my loved [brother, for] how is it since the boy heard that his sister had died and left two daughters? When he heard, he said: ‘Write to him that he may send one of them to me,’ so that I can keep her for you. He said I will take care of her like a daughter.”

P.Kellis VII 73

The two girls have been left orphaned – their father is not mentioned, but the content of the letter suggests that they were already fatherless and new arrangements for their care need to be made. The girls’ uncle will take in one of them, while Pegosh goes on to say that he will take the other sister. Such fostering (or informal adoption) of orphaned children must have taken place all the time throughout Egypt, but few adoption contracts survive. In this case, if Pegosh hadn’t been so far from home, we probably wouldn’t have heard about this situation either. More often than not, events – even tragic ones such as these – were not recorded, but were simply taken care of within the community. It is only in exceptional situations, of distance or unusual circumstances, when such matters were written down.

*Kinship terms throughout the documents may not actually refer to biological relationships, but are used as terms of endearment.

**The translations above are those of the original editors (Iain Gardner, Anthony Alcock, and Wolf-Peter Funk), whose work on these difficult fourth century texts I cannot improve – I have made a few minor adjustments only.

Technical Details

Provenance: Kellis (Ismant el-Kharab); Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt

Date: 4th century CE

Language: Coptic (Lycopolitan Dialect)

Collection: Storeroom in Dakhleh.

Designation: P.Kellis VII 73, 92, and VII 115 (sigla according to Checklist of Editions)

Some bibliography:

For Kellis’ human remains, see: S. M. Wheeler, L. Williams, T. L. Dupras, M. Tocheri, and J. E. Molto. 2011. “Children in Roman Egypt: Bioarchaeology of the Kellis 2 Cemetery, Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt,” in (Re)Thinking the Little Ancestor: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Infancy and Childhood, edited by M. Lally and A. Moore, pp. 110–121. Oxford: Archaeopress.

For child mortality and demographics generally, see: R. S. Bagnall and B. W. Frier. 1994. The Demography of Roman Egypt. Cambridge: CUP.

![SB Kopt IV 1709 [ÖNB K950r]](https://papyrus-stories.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/sb-kopt-iv-1709-c3b6nb-k950r1.jpeg)