Jennifer Cromwell

At birth, there was only a 66 per cent chance of celebrating your first birthday: one-third of all new-borns in the ancient world died before reaching that milestone. Once a child reached the age of five, their life-expectancy rose considerably, but the loss of at least one child was something that every parent experienced. While some texts mention the death of children only in passing (for example, this letter from 4th century Kellis), this is not to say that the death of a child did not leave an indelible mark.

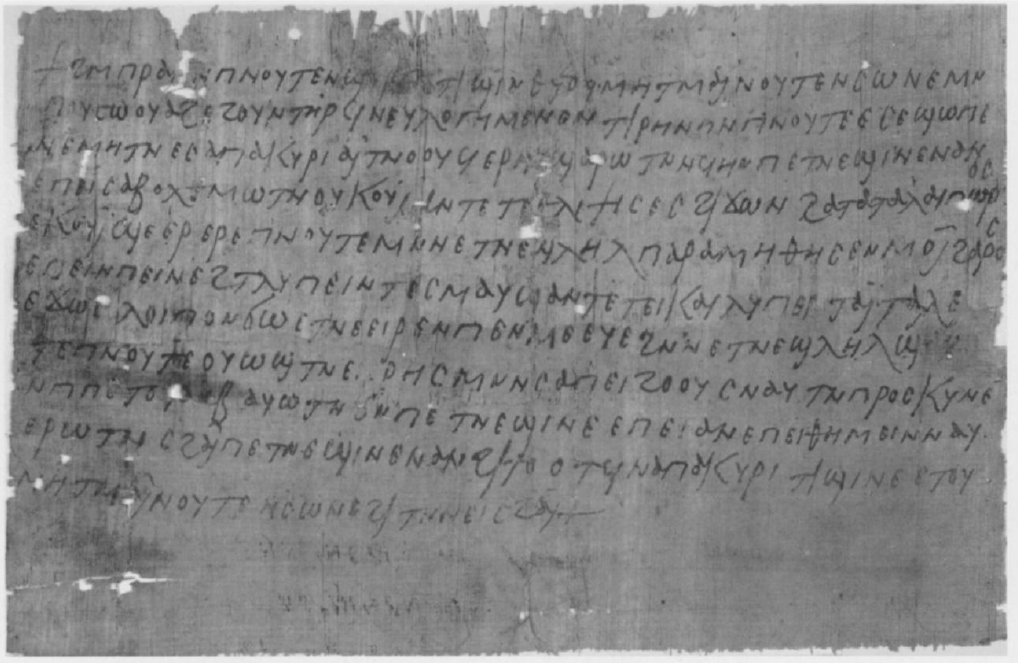

In a Coptic letter from Hermopolis, a father – unfortunately his name is not included, only the name of the man who delivers his letter – writes to a community of nuns to ask for their prayers.

“I greet your pious sisterhood and your entire blessed community. May the peace of God be with you. Here is Apakyre; I sent him south to you to bring us (back) your greeting, as without you the affliction upon us is not small, concerning the wretched little girl. May God and your prayers comfort me about her, because I could not alleviate her mother’s grief.” [SB Kopt. IV 1692]

Their young daughter had died and the father, suffering himself, is unable alone to comfort his wife, whose pain is enormous. In their moment of need, they reach out for consolation to the sisters.

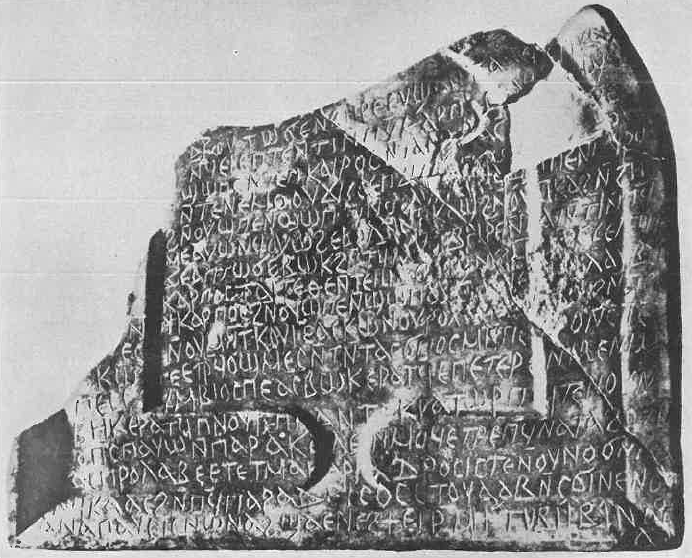

Such grief is echoed in a funerary stela written in early January of an unknown year for a girl called Drosis. While her age is not recorded, she was on the cusp of adulthood (for women, the age of sexual maturity, so between 12 and 14), before she was cruelly taken away.

“If a young plant that is protected by reeds comes to the time of bearing fruit, and if it coincides with the flooding season, such that the waters rise […and] drown it. Suddenly, grief will fall upon its owner and he will throw down his reeds, sorrowfully, because the plant has gone in its youth, before it could bear fruit. This is the case with this little girl. When she came to the age of bearing fruit, suddenly she was carried away. She was taken while in her youth, having left around her a [burning?] fire, to be extinguished by her mother and brother, with whom she lived. She went to He to Whom every breath goes, God Almighty. We beg and implore Him, now, for Ηis mercy to reach her, who has been seized prematurely – the blessed Drosis – with great mercy, and to place her in His holy Paradise, so she may find living rest forever. Written 12th Tobe, indication year 1.”

The poetic nature of this stela, with its metaphor comparing Drosis to a plant on the verge of bearing fruit, is exceptional – such inscriptions rarely record such great strength of feeling. The grief of her family, her mother and brother, is a burning fire. She was taken prematurely, but also seemingly unexpectedly, a point that may be reflected in the material aspects of the stela itself. As the image below shows, the stela is damaged in its upper left section, but the inscription itself is complete, indicating that the damage occurred before the text was incised. And even though a central area had been carved out for the epitaph, the writing actually covers the entire available surface. Did Drosis’ unexpected death force her family to buy any available stela from the local stonemason? Or, was a broken slab all that her mother and brother could afford?

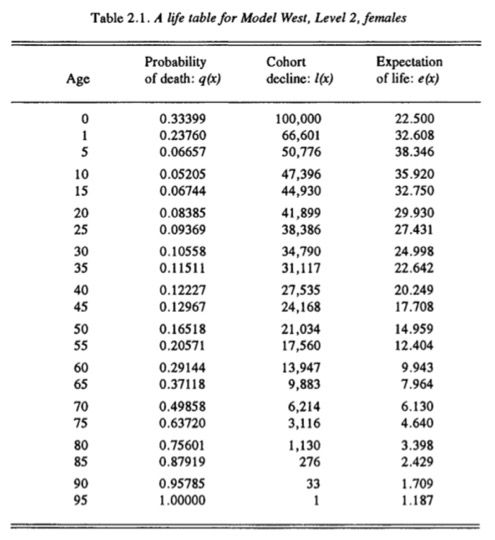

Mortality Rates in Roman Egypt

Table from Roger Bagnall and Bruce Frier (2006), The Demography of Roman Egypt (Cambridge). The second column shows the chance of survival before the next age, so:

- at birth, 33.4% chance of dying before the first birthday;

- at age 5, there was a 6.6% chance of dying before the age of 10.

The right-hand column shows how many years of life you’d have left: at birth, life expectancy was only 22.5, while if you survive until 5, you may live to be 43!

Technical Details (Papyrus):

Provenance: Hermopolis (el-Ashmunein); Egypt.

Date: 7th century CE(?).

Language: Coptic (Sahidic dialect).

Collection: Benaki Museum, Athens (inv. K2).

Designation: SB Kopt. IV 1692 (according to the Checklist of Editions).

Bibliography: Gesa Schenke (1999), “Die Trauer um ein kleines Mädchen: Eine Bitte um Trost”, in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik127, pp. 117–122 and pl. 1.

Technical Details (Stela):

Provenance: Unknown.

Date: Unknown.

Language: Coptic (Sahidic dialect).

Collection: Cairo, possibly the Coptic Museum (inv. JdE 59285).

Designation: SB Kopt. I 784 (according to the Checklist of Editions).

Bibliography: Monika Cramer (1941), Die Toteknlage bei den Kopten. Mit Hinweisen auf die Totenklage im Orient überhaupt(Wien–Leipzig), pp. 20–22 + pl. 6; Reginald Engelbach (1932), “A Coptic Memorial Tablet to a Young Girl,” in Studies Presented to F. Ll. Griffith, (London), pp. 149–151.

One thought on “Parental Grief and Child Mortality”