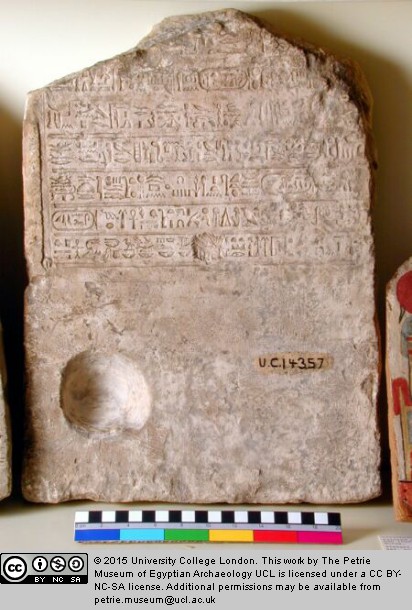

At the age of 21 years and 29 days, the sistrum-player Kheredankh died. A fragment of her funerary stela survives and is today housed in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London. Originally, this stela would have been a remarkable artefact of very fine craftsmanship, with a representation of the deceased in the presence of Osiris (and perhaps other gods and goddesses of the netherworld) in its top part, and lines of exquisitely carved hieroglyphs underneath. Of all this, little survives today, namely, only the bottom left corner of the inscription, which had been badly damaged from being reused as a door socket (as suggested by the concave depression in its corner), before the father of Egyptian archaeologist Flinders Petrie probably saw and purchased it in Egypt. Yet, even in its battered condition, this fragment still reveals the stunning quality of its original carving.

More than providing indications of the quality of its craftsmanship, the little amount of text that survives belies the significance of its content. Concerning Kheredankh herself, we know that she was a sistrum-player during the late Ptolemaic Period, a title indicating a priestess whose distinctive role was to play the sistrum, an instrument producing a rattling sound that was used during various temple rituals. The few lines of surviving text on the Petrie fragment of Kheredankh’s funerary stela provide her date of birth and time of burial, when she died in relatively early adulthood. In a touching fashion typical of such mortuary monuments from ancient Egypt, the inscription is written in the first person, as if Kheredankh herself were addressing the reader through her stela:

‘My father (…) placed <me> in the west (i.e. the necropolis). He performed for [me] all funerary ceremonies (…) I was buried in his family tomb, by the side of his male and female ancestors’.

Beyond these details, we know that Kheredankh belonged to what was probably the most prominent family—right after that of the royals—in Ptolemaic Egypt: the family of the High Priest of Ptah in Memphis, Egypt’s oldest capital and still at the time the holiest city in the whole country. The office of High Priest of Ptah can be traced back to the Old Kingdom, in the third millennium BCE, and Kheredankh’s father, the High Priest Pasherenptah III (who lived from 90–41 BCE), was to be one of the last men to hold this position, which was eventually discontinued by the Romans shortly after their conquest of Egypt in the year 30 BCE.

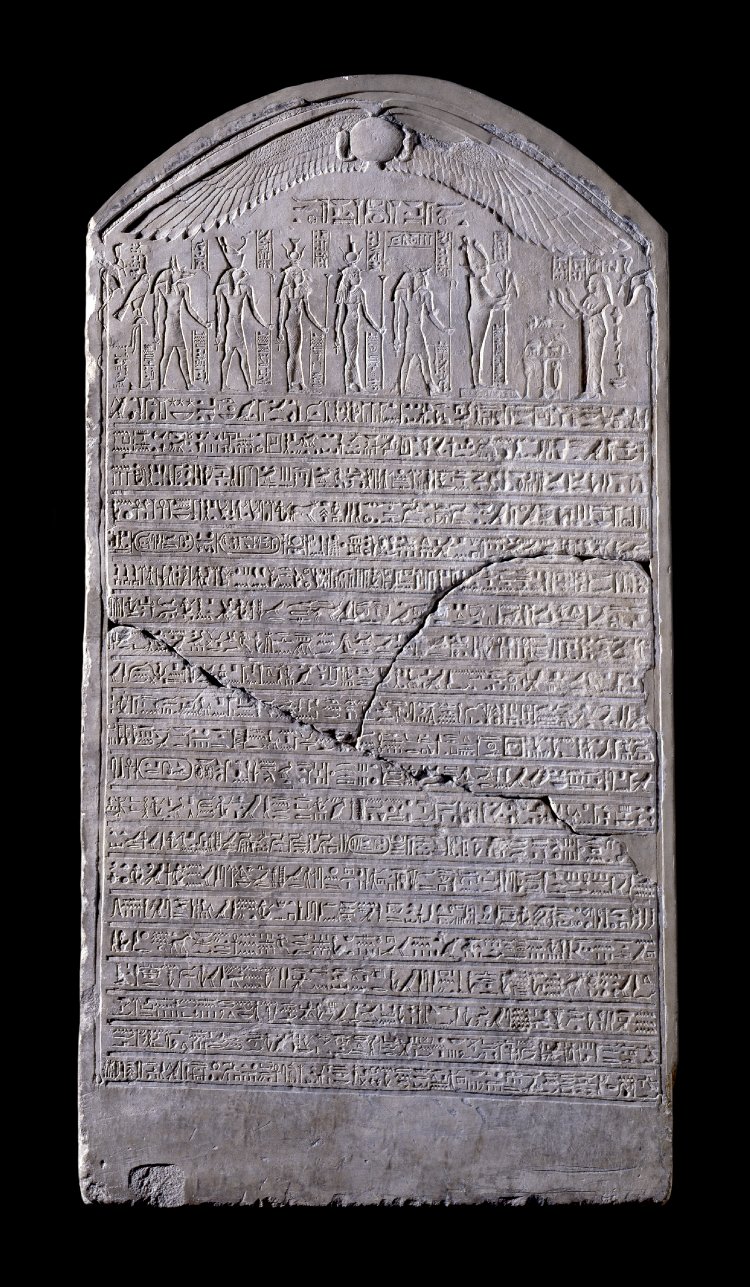

Other monuments provide us with more information about the vicissitudes of Kheredankh’s family—reminding us that objects and the stories they tell do not exist in isolation. From the funerary stela of her mother Taimhotep (or perhaps her stepmother: the lineage is not completely clear) now in the British Museum (EA 147), we know that her father Pasherenptah III was struggling to beget a male child, who would become the heir of the High Priesthood of Ptah. After giving birth to three daughters, Taimhotep and Pasherenptah III eventually turned to the gods, begging for the intercession of Imhotep, the son of the god Ptah (and, originally, an actual historical figure, a high courtier who had lived in the third millennium BCE, and the architect of the Step Pyramid of Djoser). Through a vision in a dream, Imhotep promised the High Priest a male child in exchange for works to be carried out in his sanctuary. Eventually, the god kept his word, and the couple finally celebrated the birth of their son, whom they named Imhotep-Padibastet.

While all this high-born family drama was ongoing, even more radical upheavals were about to reshape the world in which Kheredankh and her parents lived, soon changing Egypt forever. Indeed, one of the reasons to which her stela fragment owes its fame is that it is one of the relatively few Egyptian texts to contain a mention of Caesarion, the ill-fated son of Cleopatra VII and—supposedly—Julius Caesar. This mention occurs in the date given for the day of Kheredankh’s burial, which is said to have taken place in the ninth year of reign of ‘the Queen, the Lady of the Two Lands, Cleopatra, and her son […] Caesarion’, that is, in 43 BCE.

Only the previous year, on the Ides of March of 44 BCE, Julius Caesar had been assassinated in Rome, an event that had triggered a civil war, which quickly expanded from Italy across the Mediterranean. It would only be a matter of a few years before Rome’s new strong men, Mark Antony and Octavian (the future emperor Augustus) would turn against each other. Cleopatra’s private relationship and political alliance with Mark Antony, and Egypt’s consequent alignment against Octavian and his armies in the Roman West, would turn out to be fatal for her and Egypt. Following Octavian’s victory over Mark Antony, events would quickly precipitate, with Cleopatra’s famous suicide in the year 30 BCE, Octavian’s victorious entry into Alexandria, and the murder of the young Caesarion, who had by then been proclaimed king Ptolemy XV Caesarion, the last sovereign of an independent Egypt.

With the Roman conquest, many drastic changes would shake Egypt, at all levels of society. As mentioned above, the office of Pasherenptah III itself, that is, the High Priesthood of Ptah in Memphis, with its tradition dating back over more than two thousand years, would not survive the death of Caesarion by many years.

Technical Details

Provenance: Saqqarah, Egypt

Date: 14 February 43 BCE (reign of Cleopatra and her son Caesarion)

Language: Egyptian of Tradition / Middle Egyptian (hieroglyps)

Collection: Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London (UC14357)

Designation: Trismegistos TM113111

Bibliography: Jan Quaegebeur (1971), “Contribution à la prosopographie des prêtres Memphites à l’époque Ptolémaïque,” Ancient Society 3 (1972), pp. 77–109 (no. 2.5, pp. 99–100); Eva A.E. Reymond (1981), From the Records of a Priestly Family from Memphis(Wiesbaden), no. 23; Harry M. Stewart (1983), Egyptian Stelae Reliefs and Paintings from the Petrie Collection: Part Three: The Late Period(Warminster), no. 20, pl. 13.

Very nice! Is Luigi planning a new study of the Petrie piece?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just asked and he said maybe something more popular, e.g., for Egyptian Archaeology. He said the published edition and translation doesn’t need redoing.

LikeLike