Jennifer Cromwell

When dealing with ancient texts, the term ostracon refers to pottery sherds and limestone flakes that were reused to write documents. Pottery is by far the more common material used, but some areas show a particular preference for limestone. They are especially well-known from Egypt, but the practice occurs across the ancient world; see, e.g., this example from Israel. The term itself comes from ancient Greece and the practice of writing names of individuals expelled (ostracised) from Athens on potsherds.

Typically, the sherds used are large enough (or small enough) to be held comfortably in one hand. However, on occasion an abnormally large piece was used. One of the best-known examples of a huge limestone ostracon comes from late New Kingdom Egypt (ca. 1,295–1,069 BCE) and the village Deir el-Medina in western Thebes. Now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, this ostracon is about 1 m in length and bears the text of the literary work The Tale of Sinuhe. Another unusual example, this time on pottery, comes from Roman Egypt and the site of Mons Claudianus in the eastern desert. This pot was used to write two-syllable words beginning with the Greek letter pi and also has a drawing of a man. The text is written on the neck and shoulder of the original amphora, turned upside down (so the entire top section of the vessel). How was it written? Did the writer plant the narrow end in the sand in front of them as they sat cross-legged on the ground?

But what were ostraca used for? What are their modern equivalents? Being plentiful, easily accessible, and freely available, they were used for a wide variety of purposes: scrap paper, post-it notes, notebooks, text messages/SMS, postcards, cards, emails. Despite their reused nature, they could be used for correspondence between officials or receipts for purchases or tax payments, while also being used to doodle or draw cartoons. Figural sketches from the New Kingdom on limestone flakes show a range of subject matter, from the sublime to the ridiculous (including satirical cartoons showing societal and natural order turned upside-down), from the bawdy to the serious.

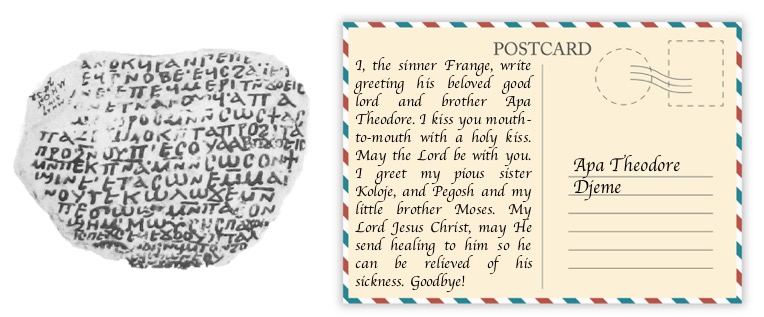

A couple of case studies written by a monk living in early 8th century CE western Thebes show the kind of day-to-day messages that ostraca were used for. Frange lived in what is now referred to as Theban Tomb 29, on Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. For most of his time there, he lived alone, but hundreds of texts written in Coptic found in the tomb and in other places reveal his social networks and how and why he interacted with people – other monks and villagers alike. Some messages were short and contained a short question or request – the kind of thing that we would send a quick text message about today. Other messages were longer, but mostly polite with generic questions about health and well-being, and maybe adding a question or two – like an ancient postcard or short letter.

Two ostraca by Frange fitting these descriptions were found from the village Djeme (Medinet Habu), a kilometre or so from where he lived. In the first, after polite hellos, he asks a man Pher to come visit him. In the second, Frange writes to Theodore, but adds greetings to other people that he knows and prays that one of them recovers from his illness. Today we have an abundance of ways to communicate such messages, in typed or handwritten form. But in the ancient world, ostraca fulfilled all these functions. Perhaps they weren’t the text message of the ancient world, but they weren’t all that dissimilar.

One of the great advantages of ostraca over other media, such as papyrus or parchment, for the study of the ancient world is their often ephemeral and informal nature. They provide a window into people’s lives that we typically don’t see from papyrus. Being more expensive and harder to get hold of for many people, papyrus documents typically contain more formal types of texts, recording major events, whether personal or public. But the stories that ostraca tell are often more intimate, revealing the minutiae of daily life and relationships, and the very real and practical concerns of the men and women who wrote them.

Technical Details (Greek amphora)

Provenance: Mons Claudianus, Egypt

Date: 2nd century CE

Language: Greek

Collection: storeroom in Qift, Egypt (inv. 7861)

Designation: O.Claud. II 415 (according to the Checklist of Editions)

Technical Details (both Coptic ostraca)

Provenance: Djeme, western Thebes, Egypt

Date: Early 8th century CE

Language: Coptic (Sahidic dialect)

Collection: Egyptian museum, Cairo? (possibly the Coptic Museum; they were returned to Egypt from Chicago after they were published in 1954)

Designation: O.Medin.Habu Copt. 138 and 139 (according to the Checklist of Editions)