In 133 CE Herakleides-Valerius, inhabitant of Antinoupolis, which had only recently been founded, put his signature to a brief document renouncing his father Herakleides’ inheritance. He came to his decision because his father had become embroiled in a protracted dispute over the state of the public archives of the Fayum. By this time, the case had dragged on for half a century, affecting two generations of multiple families, and it provides us a rare glimpse into the practical affairs of maintaining papyrus bookrolls in Roman Egypt.

It is the summer of 107, and Herakleides arrives in Tebtynis to take up his new position as keeper of the Fayum archives. He is to share his public office with another citizen, Patron, but the actual day-to-day care will remain in the hands of veteran clerk Leonides. Whereas the public office rotates on a 3-year cycle, there is much more continuity in the underlying bureaucracy. Leonides tells Herakleides that he has stepped into quite the mess: the archives have been in a poor state and deteriorating for years. In a later report, the impartial inspector Isidorus describes the situation in the following terms:

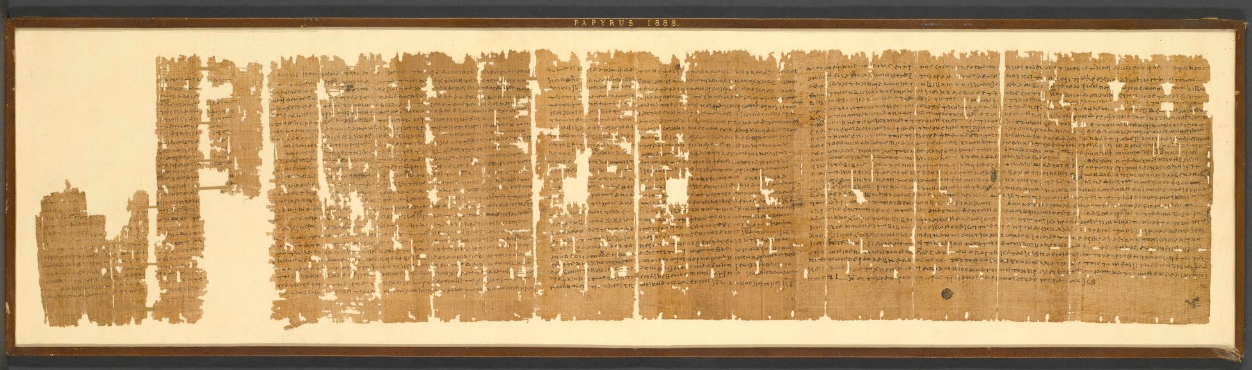

“The documents shown to me by the clerk Leonides (…) were in some cases deprived of their beginning, or damaged, or moth-eaten (…). Since the books have been hastily moved from one place to another repeatedly, lying on top of each other and unattached (…). Some were eaten away at the top because of the dry heat (…) and since they are being handled daily, and their material is brittle, it happened that some were destroyed in parts, others were without beginnings, and some had even fallen apart.”

At every change of keepers, the state of the archive was assessed, and it was at such a transition that the first documented complaint was made, almost forty years earlier in 71 CE. By the time Leonides became head clerk, the archives had apparently been handed on in ever-deteriorating condition without anyone wanting to take responsibility for the repair and reconstruction of the damaged documents. The keepers who were in charge before Herakleides had moreover decided that not they, but the clerk Leonides was responsible for the state of the archive. At some point the strategus Apollonius (a high official) decreed:

“Already before I have ordered you and I enjoin you [Leonides] now to take over the documents in their present state.”

Leonides, however, claims that in the end his employers, the public officials, must bear the responsibility. As a result, upon the arrival of Herakleides and Patron, Leonides refuses to accept any damaged rolls from the preceding keepers without the presence and permission of the new keepers. Understanding his precarious situation, Herakleides likewise refuses to take responsibility for the transfer. Leonides’ heirs later maintained

“that their father was appointed as salaried clerk to the keepers and might not be held responsible for the transfer. That, however, all the rolls were transferred except those missing the beginning or damaged or worm-eaten (…) but that the taking over was done at the risk of the responsible persons.”

The stress of the situation is enough to drive Patron over the edge, and his son Euangelos has to replace him for the final year of his tenure.

By now, the heirs of multiple sets of keepers have become burdened with stacks of old, crumbling documents that no-one is willing to take over from them. Their complaints to the strategus and prefect (governor of Egypt) are heard—in fact five successive prefects get involved! But somehow no-one manages to break the impasse until in 114-115 the prefect Rutilius Lupus puts his foot down and forces Leonides to accept all the rolls, damaged or no, from the families of the earlier keepers. The cost of repair is to be borne in part by Leonides, insofar as he accepted rolls without the knowledge of the current keepers, and in part by Herakleides and Euangelos.

Herakleides drags his feet, as evidenced by a hefty fine he pays to the dioikesis (state administration) in summer of 114, but to no avail. In the following months he too passes away, and his son Herakleides-Valerius has to pay a further fine. In the end the heirs concede, paying the required sum to Leonides for the repairs of the rolls.

Skip to 124: Leonides has also died, and the new head clerk finds a situation that still has not changed and appeals to the prefect. The judgment is that the heirs of Leonides are responsible for paying the repairs, but they can in turn privately sue the heirs of Patron and Herakleides if they deem the keepers to have been responsible. As a security, the prefect seizes both parties’ properties, in order to guarantee that they will now finally undertake the necessary work.

And a good thing that was too: around 6 months later 1 talent is raised through sale of property, most probably that of the heirs of Herakleides, since Euangelos, Patron’s heir, is penniless, and this finally paid for the necessary repairs and transfer… Or did it? Almost a decade later, Herakleides-Valerius writes:

“I cede the half due to me in the whole heritage of my aforesaid father in order not to be worried about the penalties.”

But that, finally, is the last we hear of the case in this family’s archive.

—

This ‘showpiece of bureaucratic tenacity and bureaucratic ineffectiveness’, in the words of Peter Parsons, not only documents an intriguing court case, but incidentally also contains the fullest surviving account of the practicalities of archive maintenance. The same climate that preserved the papyri to be read by scholars in the twentieth century took its toll on documents in the poorly maintained archive. We learn that documents are particularly vulnerable at their beginnings and endings, and that this is one of the reasons to create rolls consisting of documents pasted together (referred to in Greek as tomoi sunkollesimoi). Also, we hear of the possibility to reconstruct broken and damaged documents by consulting and copying master copies kept in Alexandria. No less interesting are the terms used to describe both the damage (including ‘missing its beginning’, ‘missing its ending’, and ‘eaten away at the top’) and the repairs (‘paste together’ and ‘repair’), which are otherwise rarely attested in documents or literature. A new, full discussion of the documents’ importance for these issues, together with a survey of the relevant papyrological evidence for ancient bookroll maintenance, is now available by Mark De Kreij, Daniela Colomo, and Andrew Lui 2020 (for the open access article, see the link in the bibliography below).

Technical Details

Provenance: Egypt, Tebtynis

Date: 114-133 CE

Language: Greek

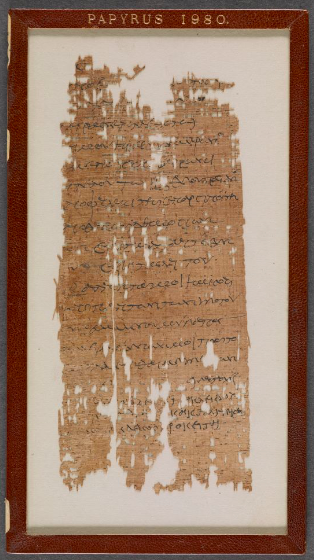

Collection: London, British Library Pap. 1885, 1980, and 1888

Designation: P.Fam.Tebt. 15, 17 (= P.Coles 20), and 24 (according to the Checklist of Editions)

Bibliography: Bernhard A. van Groningen, A Family Archive from Tebtunis (Pap.Lugd.Bat. VI)(Leiden: E. J. Brill 1950), pp. 46-62, 64-65, and 85-108; Mark de Kreij, Daniela Colomo, and Andrew Lui, ‘Shoring Up Sappho. P.Oxy. 2288 and Ancient Reinforcements of Bookrolls’ in Mnemosyne(2020), available in open access here; Peter Parsons, ‘P.Coles 20. The End of the Archives Case’ in Guido Bastianini, Nikolaos Gonis, and Simona Russo (eds), Charisterion per Revel A. Coles (P.Coles) (Florence 2015), pp. 96-102.

Hi, always i used to check blog posts here early in the morning,

for the reason that i love to learn more and more.

LikeLike