Among the most popular objects in many museum archaeology displays, the lifelike mummy panel portraits from Graeco-Roman Egypt hold a special place in the history of representing the human face. Manchester Museum’s first international touring exhibition, ‘Golden Mummies of Egypt’, offers a chance to re-examine the museum’s important collection of 10 mummy panel paintings as part of The Getty’s APPEAR project, and to consider how these objects were viewed in ancient – as well as modern – times.

A glint of light in these ancient eyes is a key element of their seductiveness; a sparkle of life not present in Pharaonic representations. Undoubtedly, a glimmer of recognition is prompted in the human brain – inviting you to wonder if you might know this person. These painted images apparently give a face to the voices of contemporary papyri; they actively invite speculation about their identities.

Most of the portrait panel mummies are not identified by name; a primary concern in Pharaonic times which is less clearly marked in Graeco-Roman Period Egypt. The accounts of Classical commentators, along with some archaeological evidence, suggests the initial installation of mummies wasin (funerary) chapels, where regular visits and rituals might occur; final deposition was made in groups. As part of an active, living tradition of ritual,perhaps it was felt that most mummies did not require individual written identification.

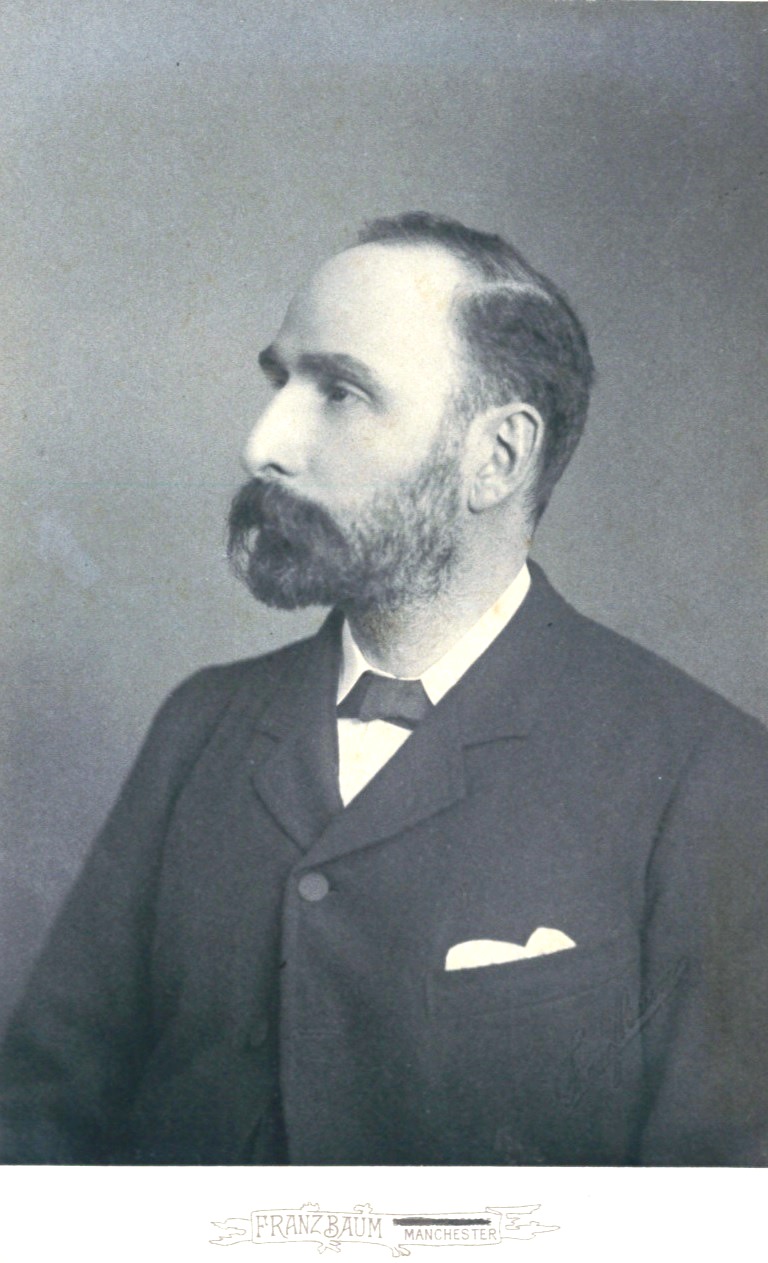

The subject in the above paintingis shown in a typical three-quarter view, as if turning to look at us. The anonymous man in this painting has curly hair and a beard. Hairstyles may suggest a particular Emperor’s reign, although precise dating is notoriously difficult with the panel paintings. Here,suggestions range from around the time of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE) and Commodus (180–192 CE). The man bears a sword belt (balteus), which may imply something of his status – although the families of all those depicted were no doubt wealthy – or an actual association with the military.

Although the technique of encaustic painting (pigment mixed with hot wax) was foreign to Egypt, the tradition of representing the deceased was not. Pharaonic representations are not ‘true to life’ in any simple way. ‘Lifelike’ sculptures placed in temples apparently show elites with the details of a real face; yet, the aim of these objects was to attract attention in scared spaces crowded with sculpture, and need not reflect anything of a person’s actual appearance.

Looking at the mummy panel paintings – saturated as we are by modern photographic reproduction and the prevalence of glazed and mirrored surfaces – we expect them to reflect a truth about ancient people as they really were. Yet, just because these are plausiblefaces does not imply that these are true, mimetic portraits in the modern sense. We desperately want them to be – that is why facial reconstruction techniques are so popular in museums and in the popular media. This modern conceit has been used as a means of testing the ‘accuracy’ of panel paintings, yet this practice has a sinister background in ‘race’ science. British archaeologist Flinders Petrie, whose Egyptian workmen found many of the panels attached to mummies at the Fayum site of Hawara (hence the common designation ‘Fayum Portrait’), was a keen believer in eugenics and regularly kept the skulls of portrait mummies to compare the two.

But, to me, these (re)constructions are subjective and contingent – they are mirages, fantasises that privilege ‘science’ and view it as a ‘magic wand’ to gain insights into ancient life. The fact that some portraits, such as this one, much resemble others – like portraits now at Eton College and sold recently at Sothebys – does not imply the existence of a group of similar-looking people, but rather indicate the production of panels that depend more on each other (or a stock type) than they refer back to the appearance of real people. Whether the panels were painted during life or posthumously is a major point of scholarly debate. The latter seems more likely to me. Regardless, they fulfilled a very ancient function by giving the deceased a visage with which to face eternity.

Too Classical for Egyptologists and too Egyptian for Classicists, the portraits have been a scholarly bone of contention for some time – yet have been a major attraction for popular audiences since Flinders Petrie exhibited those he was permitted to export in Summer 1888 at the Egyptian Hall in London, where artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema drew inspiration for their works.

There’s decent circumstantial evidence that the show was seen by Oscar Wilde – his novella The Picture of Dorian Grayappeared three years later. Such has been the impact of these haunting images on popular culture. Yet, despite repeated attempts to characterise their individual backgrounds – in terms of age, ‘race’, status – these faces resist categorisation; their inscrutability only adds to their allure.

**Addendum 22/10/21: This blog post has subsequently appeared (by permission of the author) in Shemu: The Egyptian Society of South Africa’s Quarterly Newsletter 25/4 (October 2021).

Technical Details

Provenance: Hawara(?), Egypt

Date: Second half of second century CE

Technique: Encaustic pigment on lime(?)wood panel

Collection: Manchester Museum, inv. 11306, University of Manchester, UK. From the collection of Max Emil Robinow (1845-1900), a German émigré who settled in Manchester in the 1870s and travelled in Egypt in 1896. This piece likely derived from Flinders Petrie’s purchasing of antiquities in the Fayum region. Its rounded top suggests that it most probably comes from the site of Hawara, where Petrie worked for three seasons. Robinow was likely introduced to Petrie through a major sponsor of his excavations, the Manchester cotton magnate Jesse Haworth.

Bibliography: Barbara Borg, Mumienporträts: Chronologie und kultureller Kontext(Mainz: Philipp von Zabern., 1996), pp. 16, 80, 156–7; Campbell Price, 2020. Golden Mummies of Egypt. Interpreting Identities from the Graeco-Roman Period (Nomad Exhibitions/Manchester Museum, 2020), pp. 160-195.

2 thoughts on “Facing the Dead? Framing Mummy Panels from Hawara”