Jennifer Cromwell

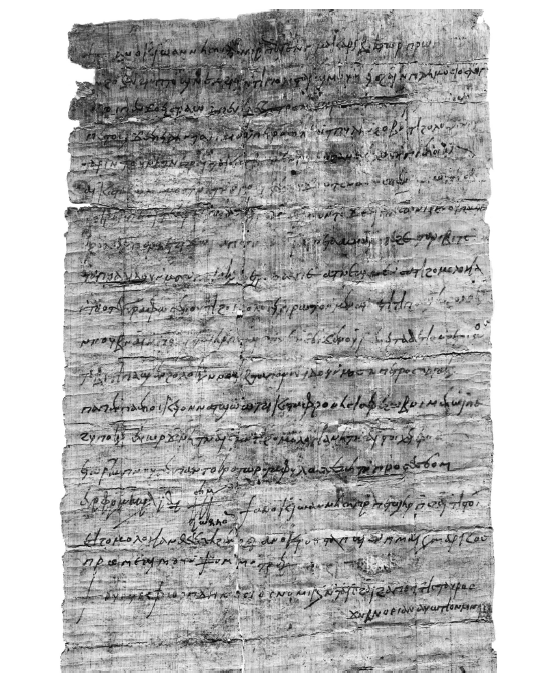

The Roman fort Vindolanda is located just south of Hadrian’s Wall in northern England. Occupied approximately from 85–370 CE, the fort guarded the Stanegate, the Roman road that ran from the River Tyne to the Solway Firth. In addition to the archaeological remains of the site, a large number of Latin texts written on postcard-sized thin wooden boards provide snapshots of daily life on the Roman frontier. While Vindolanda was a military outpost, the tablets don’t just talk about military affairs. The officers stationed at the fort lived there with their families, and letters, lists, and other records give remarkable insights into their lifestyle and social and economic activities.

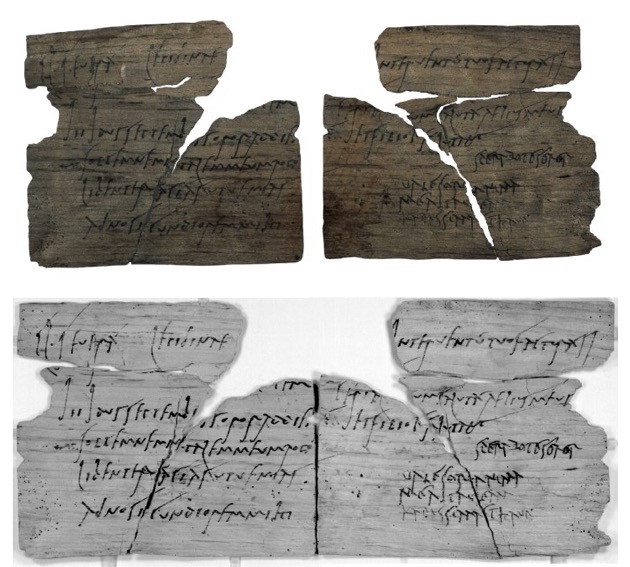

One day in late summer, Claudia Severa, wife of Aelius Brocchus, wrote to Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of Flavius Cerialis, inviting her to come to Vindolanda to join her birthday celebrations on 11th September. This invitation is perhaps the best-known of the Vindolanda tablets, and is probably the most striking text to a modern audience, with its recognisable activity and presentation of personal relationships.

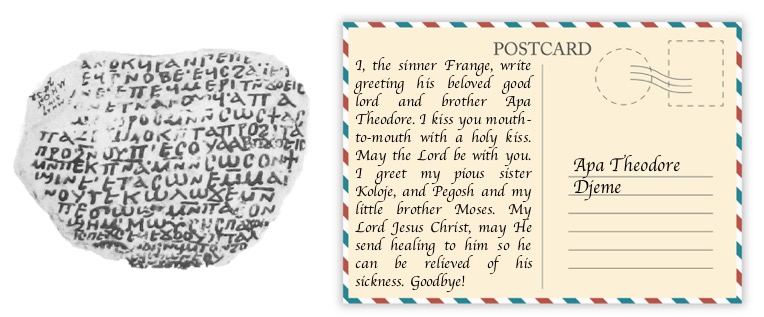

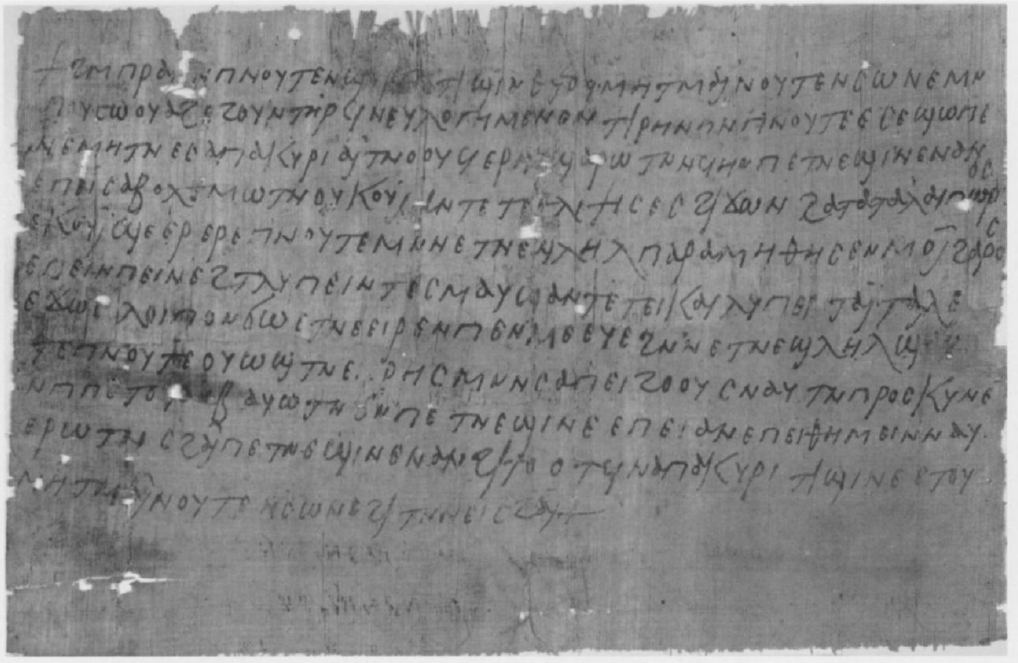

“Claudia Severa to her Lepidina, greetings. On the third day before the Ides of September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present(?). Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him (?) their greetings.

I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.

To Sulpicia Lepidina, (wife) of Cerialis, from Severa.” (translation: Bowman 1994)

This party invite isn’t our only evidence for Romans celebrating the birthdays of individuals. Latin birthday poems were written by authors such as Horace, Ovid, and Martial in honour of the birthdays of particular people – and the poems themselves are often intended as birthday presents. These poems give us an idea about how Romans celebrated, by wearing white clothing, bedecking an altar with garlands, burning incense, and sometimes eating cakes and drinking wine (as we see in Ovid’s poems Tristia III.13, about his own birthday, and Tristia V.5 about his wife’s).

Severa didn’t live in Vindolanda but in another fort, Briga – one of the places named in the tablets that hasn’t yet been identified (the word is a common Celtic place-name meaning ‘hill’, but which hill?). Did Lepidina join the birthday party? We don’t have any definite proof, but other letters between the two women indicate that they did regularly travel to see each other, as Severa notes in another letter: “just as I had spoken with you and promised that I would ask Brocchus and would come to you, I asked him and he gave me the following reply, that it was always readily permitted to me … to come to you in whatever way I can” (T.Vindol. II 292; translation Bowman 1994). Hopefully Lepidina was able to make the party and eat cake and drink wine with Severa!

One final point about this letter needs to be made. While most of the letter is written probably by a professional scribe, Severa wrote her final greeting herself. Her personal note to Lepidina is written in the bottom right side of the tablet. Apart from being an indication of her affection for her friend, this short message is the earliest known example of writing in Latin by a woman. It’s not just the words that are important for our understanding of life in the ancient world, but how they were written as well.

Technical Details

Provenance: Vindolanda (Chesterholm), England

Date: 97–103 CE

Language: Latin

Collection: British Museum (inv. 1986,1001.64)

Designation: T.Vindol. II 291 (abbreviation according to the Checklist of Editions)

Bibliography: Kathryn Argetsinger (1992), “Birthday Rituals: Friends and Patrons in Roman Poetry and Cult,” Classical Antiquity 11/2: pp. 175–193; Alan Bowman (1994), Life and Letters on the Roman Frontier (London: British Museum), p. 127 (#21); Alan Bowman and J. David Thomas (1987), “New Texts from Vindolanda”, Britannia 18: pp. 137–139 (#5); David Campbell (1994) The Roman Army, 31 BC – AD 337: A Sourcebook (London: Routledge) #254.